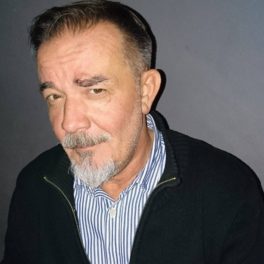

Nikolina Andova Shopova was born on 3 February 1978 in Skopje. She graduated from the Faculty of Philology (Macedonian and South Slavic literature) at the St Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje. She has published two books of poetry „The entrance is on the other side“(2013) and „Connect the dots“ (2014). Her first book „The entrance is on the other side“ was awarded with the prestigious award „Bridges of Struga“ in 2013, award of UNESCO and the Struga Poetry Evenings for best debut book, and is published in English language. In 2014 she published the second poetry collection “Connect the dots”, which is also published in Serbian language. In 2016, a selection of her poetry in English, Macedonian and French is published by Éditions Bruno Doucey. Her poems take part in many anthologies of Macedonian poetry. They are translated into many world languages and she is a participant in many poetry festivals across Europe.

In 2019 she received the “Novel of the Year” award, for her first novel “Someone Was Here“, awarded by the Foundation for promotion of cultural values ”Slavko Janevski”. She also writes short stories and picture books for children.

„Connect the dots“ (2014). Her first book „The entrance is on the other side“ was awarded with the prestigious award „Bridges of Struga“ in 2013, award of UNESCO and the Struga Poetry Evenings for best debut book, and is published in English language. In 2014 she published the second poetry collection “Connect the dots”, which is also published in Serbian language. In 2016, a selection of her poetry in English, Macedonian and French is published by Éditions Bruno Doucey. Her poems take part in many anthologies of Macedonian poetry. They are translated into many world languages and she is a participant in many poetry festivals across Europe.

In 2019 she received the “Novel of the Year” award, for her first novel “Someone Was Here“, awarded by the Foundation for promotion of cultural values ”Slavko Janevski”. She also writes short stories and picture books for children.

Someone Was Here

excerpt

As I opened the peapods to roll the little balls into a plastic dish, I hoped that when I pulled the pod apart I would find something else, something that would surprise and excite me. Something that according to all the laws of nature shouldn’t be there, and precisely that thing had decided to reveal itself precisely to me. From that entire mountain of green pods waiting to be opened, I would discover just the one that held within it something unusual, something wondrous that had not yet appeared before my eyes, so I raced to open them, digging my fingers into the seams and tearing open the pods. My fingernails were green, and they hurt from the dried bits that wedged underneath them, but I was determined to reach the one I was looking for. My mother was shelling peas opposite me and she watched me bustling, thinking I was interested in counting and rolling the little balls which were strung through the pods like ball earrings. The unopened pods in the bowl were decreasing, as the volume of green balls was growing along with my impatience, and when I rolled out the last pea, I looked in defeat at the floor, hoping I would catch sight of an unopened one. But everything was opened and shelled, and the world became once more dreary, empty, revealed, with no hidden meaning or significance. The riddles and secrets that I sought everywhere around me, even in these small rituals, seemed ever further from me, in some other place, outside my view and grasp and I tried to create them for myself, weaving a mysterious veil around things that were seemingly ordinary and every day. With my fork I created a castle out of the mashed potatoes on my plate because I was obsessed with the scene in the movie “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” which ran for a week in the evenings while my father was in the hospital, the one in which Roy makes a mountain out of his mashed potatoes and other strange things after he saw something unusual in the sky. I pretended that I, too, had experienced something similar that I could not explain to myself, but which tormented me, and I inverted a cardboard egg carton and used the inverted holes like а keyboard which I covered with non-existent letters and then used to communicate with my imaginary creatures from another planet. Empty egg cartons had been put out in the shed and the stack of them, which was about as tall as I was, kept growing smaller as I took new ones, because I quickly tore and made holes in the old ones by writing and typing on them. When the pile had been reduced to the height of a small chair, my father died. I was sitting on them the day his body was laid out in its coffin in the living room like some sort of museum exhibit which everyone came to see; some even to touch and stroke it, while my father, for the first time in his life and certainly for the first time in his death, kept silent for so long and had no comment for anyone about anything. My mother sat in the dining room with her head leaning on my aunt’s hip, they tightly held each other’s hands and they dried their eyes with damp and half-torn paper napkins as they silently peered into space. Whenever my mother glanced at me, she would cry harder and pull me to her lap, but I finally ran off to mingle with the people coming in and to sneak out the door and run to the garden shed. It was twilight but I was used to the dark and the darkness was perhaps the only thing I wasn’t afraid of. I was more afraid of staying at home, of seeing my father lying in his coffin with gauze tied around his head, dressed in the suit he saved for special occasions, and of hearing the sobs that would swell like a powerful wave when new people came in the open door. I was suffocated by the smell of burned coffee and candles mixed with the stale scent of old women and old men, who would pat my head and press themselves to my face whispering something which I didn’t want to hear or understand. I didn’t want to hear the muted but cruel whispering of Auntie Žana, who was sitting not far from my mother, waving and tapping her finger on the dining room table arguing about something with the woman sitting opposite her and spraying spittle on the cookies that had been laid out for his soul. I had to disappear as quickly as possible, and although the egg carton keyboards poked my behind, I felt an inexplicable combination of sadness, comfort, and freedom then rocked by these emotions, I fell asleep leaning against the peeling wooden rack which held the things that were spoiled and unusable, but which we’ve kept for years just in case they were needed.

I woke with the thought that my mother was crying and in despair because she couldn’t find me, and I dashed to the front door which was still open. I burst into the living room and my aunt ran up to me asking whether I had rested up, likely thinking that I had been asleep in the bunk bed in the children’s room. I didn’t respond, I just ran towards the bedroom just as our neighbour, a nurse, came out and signalled me with her hand to be quiet because my mother was sleeping. The coffin was in its old place, this time closed like a pod, and I felt the prick under my fingernails. Some of the people had dispersed, it smelled of smoke and staleness, and that moment I knew that home would never again be home.

“Has this child eaten anything?” asked one of the old women and my aunt sat me at the small table in the kitchen, moved the ashtrays and cleared the table of the discarded wrappers of chocolate coffee-candies, and brought me some of the cheese pastries and some foil-wrapped wedges of processed Zdenka cheese that she was getting ready to bring to the cemetery.

“We lose; our whole life we lose something,” said the man standing by the window smoking. There were only the three of us in the kitchen and I imagined he was addressing my aunt, since he either didn’t notice me or he was pretending I wasn’t there. I didn’t know him, and I thought he was one of my father’s colleagues, because he wasn’t sitting in the living room with the other relatives.

“Folks, friends, you’ll lose your wife, you’ll lose your husband, work, house, property, children…training is what it is, training… So you get accustomed to it, you get accustomed to losing, for when the time comes that you lose your life as well, so you can let it go and not cling to it like a blind man to a stick,” he said curtly and blew the smoke through the window. My aunt opened and closed the oven, checking the cheese rolls so they didn’t burn, and I sensed she wasn’t listening to him, but out of kindness shrugged her shoulders and nodded her head with pursed lips.

“Because, if you don’t let go of life, and your time has come, you’re already dead, and even then…even then…” he considered how to finish the sentence, “even then you’ll have a problem,’ he said quietly, while stubbing out the butt in the ashtray. He said this more for himself, as if he wanted to make the point to himself and to spare us further explanations. With a look I asked my aunt, “who is this?” as he stood with his back turned and looked through the window, my aunt answered me back, also by a look and a gesture.

***

It’s not as if I hadn’t thought of this before, but I was determined not to accept the invitation which I knew would inevitably arrive one day. Vania proposed that the three of us meet: her, me, and the owner of the apartment; we should go out somewhere for a drink because she’s heard about me constantly and said that she wanted to meet me at last. We had already been in her personal space, anyway, and this was an entirely expected and logical course of events.

I got out of it by saying it would be very unpleasant and at the moment I wasn’t ready for such a meeting, because, until recently we had been seeing each other in her apartment. But I added that in the future, after some time had passed, I’d have no problem meeting her, or sitting together somewhere, the three of us, to chat and laugh, and at the end we would pay her bill since she had been so nice to us and had unselfishly let us use her place temporarily. Vania looked at me with approval and smiled contentedly as if she had expected this answer or as if she should have assumed it, knowing my sensitivity and attention to such things. The truth is that I had never intended to become acquainted with her in the context she wanted and anticipated, and maybe I never wanted to meet her at all. I wanted to touch the things she touched every day, to melt in the bodiless embrace of her shirts and coats on the hanger, to drown in the depth of the armchair, where I supposed she most often relaxed, to touch my lips to the dried traces of lipstick on the not-quite clean glass and to place my head on her pillow, which smelled of faint smoke and of hair. I did not really want to touch her hand, I hadn’t wanted to embrace her if she were standing in front of me, kiss her, or catch her scent. I wanted to caress her reflections, just as I enjoyed doing in Natalie’s room, the room Irina did the least to keep clean and tidy, so as not to wipe away her smell, and through this, her presence, which, most likely, only she and I sensed in our nostrils. Natalie’s room was the only one that didn’t smell of cleaning products, and I would go in to stroke the toys she had played with, her small many-coloured dresses, and her other clothes which we hadn’t wanted to give away, the little notebook with a red band in which there were drawings of Irina and me holding hands, with arrows that had written above them in green coloured pencil – mama, papa. I would curl up like a fetus on her little bed on the blue sheets jammed full of little gold stars and I would lie there for hours, calm and assured that I would not have to say goodbye to it, too. The objects and the material on which I lay would likely outlive me too, and no one would be able to take these things from me. With them I was secure. And for me, that was enough.

***

My mother was convinced that cigarettes had killed my father, although the doctors said that the cancer in his lungs was an illness that could arise from other factors as well. “If I ever see you with a cigarette… .it’ll be too bad for you!” she would warn me, but this sounded both tragic and funny to me because, unlike my father, she couldn’t frighten me with any specific punishment, she was too gentle and tender to think up something, let alone pronounce it or execute. “It’ll be bad for you,” was the most terrible threat she could direct at me, even when I had done something for which I really did need to be punished. I wasn’t accustomed to the freedom I had after my father died, and everything I had longed to do, and which had been forbidden, had not brought me the anticipated happiness and pleasure, and it bored me quickly. I splashed my cheeks and my neck with his aftershave from the small green glass bottle, without afterwards washing and scrubbing my face with soap and water afraid that he would smell me and turn my face red from pain. I opened the brown cardboard files he had carried to work but which I couldn’t touch, I sat until late at night and watched television in his armchair with the remote in my left hand just like he used to do, and I would curse like him if one of the buttons in the remote got stuck or didn’t work. “Oh mother – where’s it gotten stuck. Ah, there it is!”, he would pull out the grey button with the nail of his pinky finger, which I thought he grew out just for that purpose. Every so often I would peel off the thick brown layer of tape that held together the bottom of the remote, and I would put on new tape, with pride as if I were accomplishing who-knows-what sort of craftsmanship. Before I fell asleep, scenes from the films I had watched until late at night would return to me, not that I fully understood them, but because that’s what he watched. The images of Papillon in solitary confinement when, out of starvation, he caught a cockroach, or the village idiot Michael who dragged his leg across the sand in “Ryan’s daughter” circled my conscience jumbled together with images from the burial and flies on the wall. I tried lying down on the lower bunk of the bunkbed and fell asleep with the light still on, but that didn’t suit me very long, and after only a few evenings I returned to the upper bunk and put out the light early. I stripped the stem of the ferns with only one stroke of my hand, and I knew that my mother would pretend she hadn’t noticed the thin, naked stems sticking out from the greenery. With a felt-tip pen I scrawled things on the thick leaves of the rubber plant , or I’d write my name amid the veins of the large Elephant Ear plant, just because no one stopped me. I splashed through the yard in his rubber flip-flops as tiny stones poked through, and I sprayed the hose high into the trees. Through force of habit I did my lessons and I studied in the kitchen or in the dining room as I had before so I would be noticed, even though there was no one to notice me. My mother was at work all day; she returned tired and was only interested in whether or not I had eaten. She routinely checked whether I had eaten the sandwich she made for me every day to take to school wrapped in the blue-white plastic bags with “milk” written on them, which she kept rolled in an elastic band to have for packing meat for the freezer. She prepared lentils with lots of garlic and little hot sausages and leeks, since that was my father’s favourite. A whole pot would be left over because neither my mother nor I ate garlic, but she stubbornly kept making the same dinner every Sunday, as she had when my father was alive. His coat hung on the hanger behind the door. I asked why she kept washing the coat since no one was wearing it, and she said to me as she was wringing out the sleeves over the washbasin: “Something might have crawled in… a spider, a centipede, everything in the house is damp.” When she dusted, she moved aside the carton still containing a few cigarettes, and then she would put it back beside the vase on the small table.

I waited to find a suitable moment to mention to her what Emil had told me about his aunt, and to convince her that we should buy human masks somewhere so that my father’s spirit wouldn’t inhabit us, or we should buy at least one “bad” one since my father was bad, too. One evening, as she pressed down the orange-coloured toaster with her elbow, I said this to her; she was visibly upset and said she didn’t want to hear about doing these “devil things”. Аnd she scolded me for what I had said about my father, adding that he wasn’t at all a bad person.

“You should know how much good your father did, how many people he helped,” she said with hidden pride. “All right, he did have a temper, both good and bad, like everyone else. Take Žana, everyone considers her a force of evil, she poisons animals in the neighbourhood, not that she isn’t a snake at times, but she gives her soul for people. She made woolen knee socks for the children who live beside her, those poor things who were left without a mother. She brought them dinner, gave them money, as much as she could… But your aunt, you know what she’s like, gentle, kind, but something once got into her head and she said something she shouldn’t have, she did something she shouldn’t have, and now, everyone thinks she’s a wicked person.

Then she added that my father was in heaven and I shouldn’t worry that some sort of spirits were going to inhabit me, and then I recalled how at the burial one of his cousin’s had come up to me and grabbed my chin, looked me right in the face with her red eyes and said to me tearfully: “You are just like your father. The spitting image!” That was the first time anyone had told me I looked like my father and I was afraid that maybe it was too late and that he had already gotten inside me; At such moments I missed Emil most of all; he would surely have understood me and would have known what I should do. And if he didn’t know, he wouldn’t be ashamed to ask someone and then run back with the answer, like he always did. Now I had to sort it out myself, and I was afraid to call the spirits the way Emil and I had done, so I went out to the shed where the old rusty shower nozzles with their tangled hoses were kept along with broken telephones, or just their receivers. I decided to use them to attempt to contact my father to see whether he really was in the sky or inside me, and although I knew this wasn’t the way one called to a spirit, it’s like I wanted to act out pretend courage for myself, like I was doing something that only fearless people would dare to do. As I pulled the box from the top shelf, countless small screws and a crumpled, dried up tube of glue rattled to the floor. I knew that it was my carelessness that had knocked over the small glass jar they spilled from, but still my hand shook as I held the boxy red telephone receiver that had turned dark from storage and dust.

“Vasil…Vasil…” I whispered into it, calling my father by his name for the first time.

“Vase, are you listening to me?” I said, using the nickname my mother called him. I took out the old handheld shower nozzle which looked like a telephone receiver and I repeated the same thing, but all there was on the other side was silence.

After a short time, my mother stopped making lentils with sausages every Monday, the coat behind the door and the box of cigarettes which stood on the small table seemed to have disappeared and only then did I feel that father had truly died.

Translated by Christina E. Kramer